I love celluloid film. I love its smell, the satisfying ritual of loading a roll into my camera, and most importantly the look it produces—especially in black-and-white photography. There’s a particular honesty to a strip of film. Silicon sensors record; emulsion interprets. That difference sounds poetic, but it is actually chemistry. Black-and-white film contains silver halide crystals suspended in gelatin; light strikes them, rearranges atoms, and you quite literally grow an image out of metal. Photography began as alchemy and, stubbornly, it still is.

When the shutter opens, light hits the emulsion and changes those silver crystals at a microscopic level. Nothing visible appears yet; what you have is a latent image—a hidden map of light stored inside the film. During development the film is placed in a chemical developer, which reduces the exposed silver halide crystals into pure metallic silver. The areas that received more light turn darker because more silver forms there. After that, a stop bath halts the reaction, and a fixer dissolves the unexposed crystals so they cannot continue reacting to light. What remains is a stable negative: bright parts of the real scene appear dark on the film, and shadows appear clear. You have not just saved a picture—you have physically altered matter according to the light that once existed.

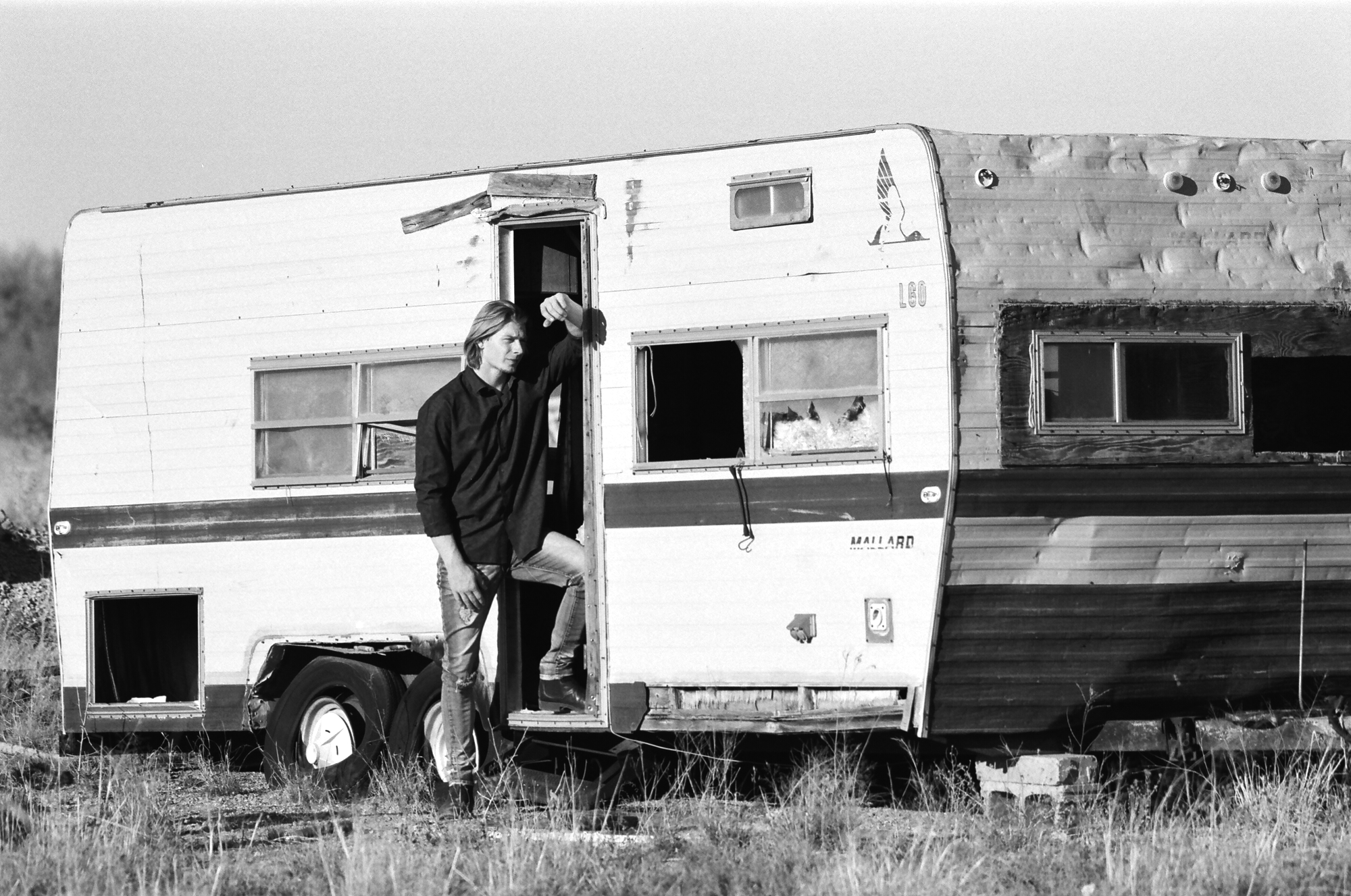

Film consistently renders black and white in a way digital still struggles to match. It handles highlights gently, lets shadows fall off naturally, and carries texture instead of electronic noise. Skin looks like skin, clouds hold depth, and darkness feels dimensional rather than empty. That is exactly why manufacturers such as Leica continue to produce dedicated monochrome cameras and charge a premium for them. If black-and-white photography were truly dead, companies would not invest in designing tools built solely for it.

The image is only halfway finished at the negative stage. To make a photograph, the negative is placed in an enlarger—a projector for film—and light is shone through it onto photographic paper coated with a similar silver-based emulsion. Where the negative is dark, less light reaches the paper; where the negative is clear, more light passes through. The paper is then developed just like the film: developer reveals the image, stop bath freezes it, and fixer makes it permanent. Watching a print slowly appear in the tray is one of the quiet miracles of photography. The image doesn’t come from a printer head or a screen; it emerges from light interacting with chemistry in real time.

Film does not just carry an old-school appeal; it changes how a photographer behaves. With only a limited number of frames, you slow down. You watch the light longer. You wait for expression, gesture, and timing. Each exposure becomes a decision instead of a reflex. In many ways it is actually simpler than digital. You stop chasing menus, histograms, and the rear screen. You trust your camera and your light meter, and more importantly you trust your own judgement.

The final print is not merely a reproduction. It is a physical artifact created by the same light that once bounced off the subject and traveled through a lens. The photograph is not a file describing reality—it is a trace of reality itself, fixed in silver and paper, a small piece of time you can hold in your hands.