Mentally Forgotten

I was fifty years old before I finally got the answers I didn’t even know I was searching for. Bipolar disorder, anxiety, and depression—those three diagnoses hit me like a freight train. Suddenly, the decades of confusion, pain, and chaos made some kind of sense. But by then, the damage was already done. I had lost everything that mattered: my family, my home, my sense of self. I found myself on the streets, alone, cold, and broken.

It’s a terrifying thing, being homeless. You become invisible. People pass by, pretending not to see you, like your suffering might be contagious. But I wasn’t just some man who had given up on life. I was someone who needed help, who had slipped through the cracks over and over again.

Because of my story, the nightmare I lived longer than I wanted to, being a photojournalist at heart allowed me to connect to the people around me. I had a small film camera and through the lens I was able to view my world—using the lens very much like a shield to protect myself from the reality I was facing. At the same time I was heartbroken for myself, but I found myself even more heartbroken for the people I was essentially living with at the shelter.

I say “living with” but that’s inaccurate. The shelter is where I was able to start the process for getting a small amount of help in the form of a referral to an actual doctor. I was fortunate. I had a car to sleep in, where most did not. While at the shelter I connected with my fellow homeless humans. I learned about them, their lives, their horrors, and their traumas. It was then that I knew I had to do something, but I had no idea what it would be. All I knew was that I could tell a story—in this case, a part of my own story wrapped around the story of others. That is where this photo-essay began.

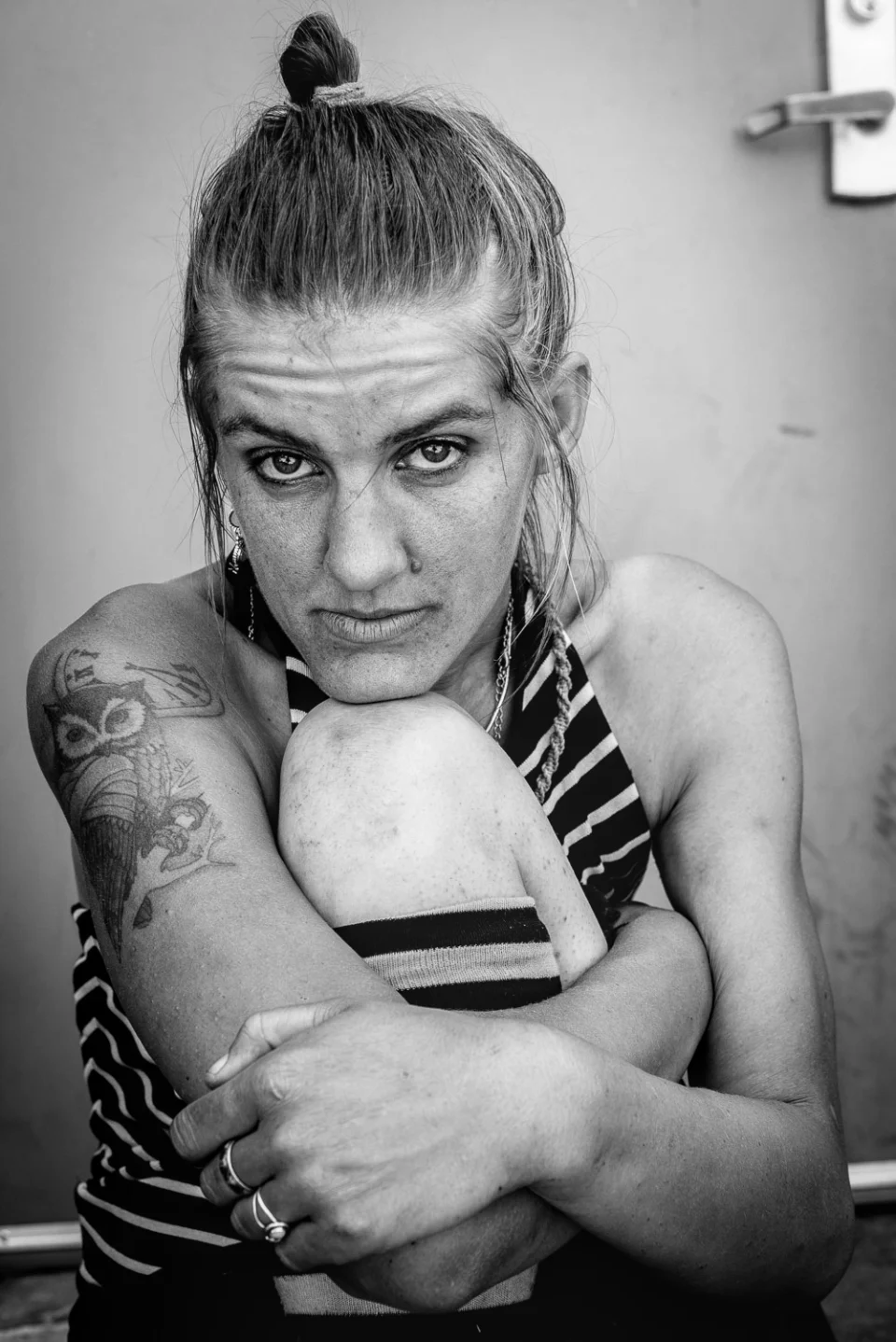

The Mentally Forgotten photo-essay began as a means to tell the story of those forgotten by society—the people who are easily dismissed and ignored because they look different or are in need. People who are not in their shoes often turn away, afraid they may be asked for something for free. I’ve been working, as best I can, on this photo-essay for a number of years now, and due to circumstances beyond my control, I have not been able to fully engage in its progression.

That is about to change. I have picked my cameras back up after leaving college where I earned my Emergency Medical Technician certification (NREMT) and my wildland firefighter certifications. I had to put my cameras down to focus on those tasks, which were difficult to say the least. But now it’s time to pick up the story again and tell the stories of those who do not have a voice of their own.

There is a substantial amount of controversy regarding making images of the homeless, suffering, and downtrodden among photojournalists and street photographers. They have the luxury of voicing their opinions and criticizing people who they believe are taking advantage of others for the sake of a dramatic image. And I agree with them. But, I was homeless. I lived on the street. I was taken advantage of. And I know how important it is to tell these stories the right way—with respect and dignity for others. That’s the difference: when you’ve experienced it, you know how to help those who are living it.

I was mentally forgotten by friends and family because of my own mental illness. On the streets, I found others that were mentally forgotten as well—and who should never be. I was one of the lucky ones.

A kind soul saw something in me—a human being worth saving. They took me in, gave me shelter, and more importantly, helped me get the treatment I so desperately needed. That act of compassion saved my life.

But most people aren’t so fortunate. Runaways, many of them escaping abuse, end up trading one nightmare for another on the streets. The mentally ill wander, untreated and misunderstood, with no place to go and no system to catch them. Veterans who once served with honor return home only to be discarded when they no longer fit the mold. And those battling addiction—often a symptom of trauma and pain—are treated like criminals instead of patients in need of care.

What ties us all together is not just the suffering, but the neglect. The government’s response? A patchwork of underfunded shelters, red tape-laced programs, and empty promises. There is no real safety net. No national urgency. Just silence.

People say we live in the greatest country in the world, but what kind of greatness lets its own people rot on sidewalks? Where is the dignity in letting a veteran sleep under a bridge or allowing a teenager to sell themselves just to eat? Mental illness, addiction, trauma—these are not moral failings. They are illnesses. They require treatment, not punishment.

My story could have ended very differently. And for far too many, it does. We need more than thoughts and prayers. We need action. We need a system that sees the humanity in every soul, especially the ones we so easily ignore.

I survived. But survival shouldn’t depend on luck. It should be a right.

If we truly want to call ourselves a civilized society, we must start acting like one. The time for compassion is now.