Photography did not begin in color. It began in light.

Long before software sliders and preset packs existed, photographers worked with luminance — the simple recording of how much light struck a surface. Black-and-white photography is not the absence of color; it is the concentration of information. Without color to guide the viewer, the eye begins to see shape, contrast, texture, and emotion more clearly. Lines become stronger. Faces become more expressive. Light itself becomes the subject.

I prefer black-and-white imagery, though I do photograph in color when the subject calls for it. When I commit to black and white, however, I do not convert a color file later. I photograph on true monochrome film. The reason is not nostalgia; it is physics.

Digital cameras are designed to see color. Nearly all of them use a color filter array — commonly called a Bayer filter — placed over the sensor. Each pixel records only red, green, or blue light. The camera’s processor then interprets and reconstructs that data into a full image. When a digital photograph is converted to black and white, it is not actually monochrome. It is a translation from color information into grayscale. The photograph is calculated.

Film works differently. Black-and-white film does not separate light into color channels. It records light intensity directly through silver halide crystals in the emulsion. There is no interpretation stage and no algorithm deciding tone relationships after the fact. Light strikes the film, and the film responds. The result is a direct record of luminance rather than a reconstruction of color.

That difference matters visually. True black-and-white film produces a distinct tonal separation, micro-contrast, and edge clarity that digital conversion struggles to replicate. Digital monochrome can look smooth and clean, but it often appears slightly softened because it began as color information. Film, by contrast, has structure — a fine grain that holds detail and gives depth to highlights and shadows. It renders atmosphere instead of approximating it.

This changes the way a photograph is made. Shooting monochrome film forces intention. There is no checking the rear screen and correcting later. Exposure must be judged carefully. Light must be read. Composition must be decided before the shutter is pressed. The photograph is created in the moment, not constructed afterward on a computer. Editing still exists, but it is refinement, not rescue.

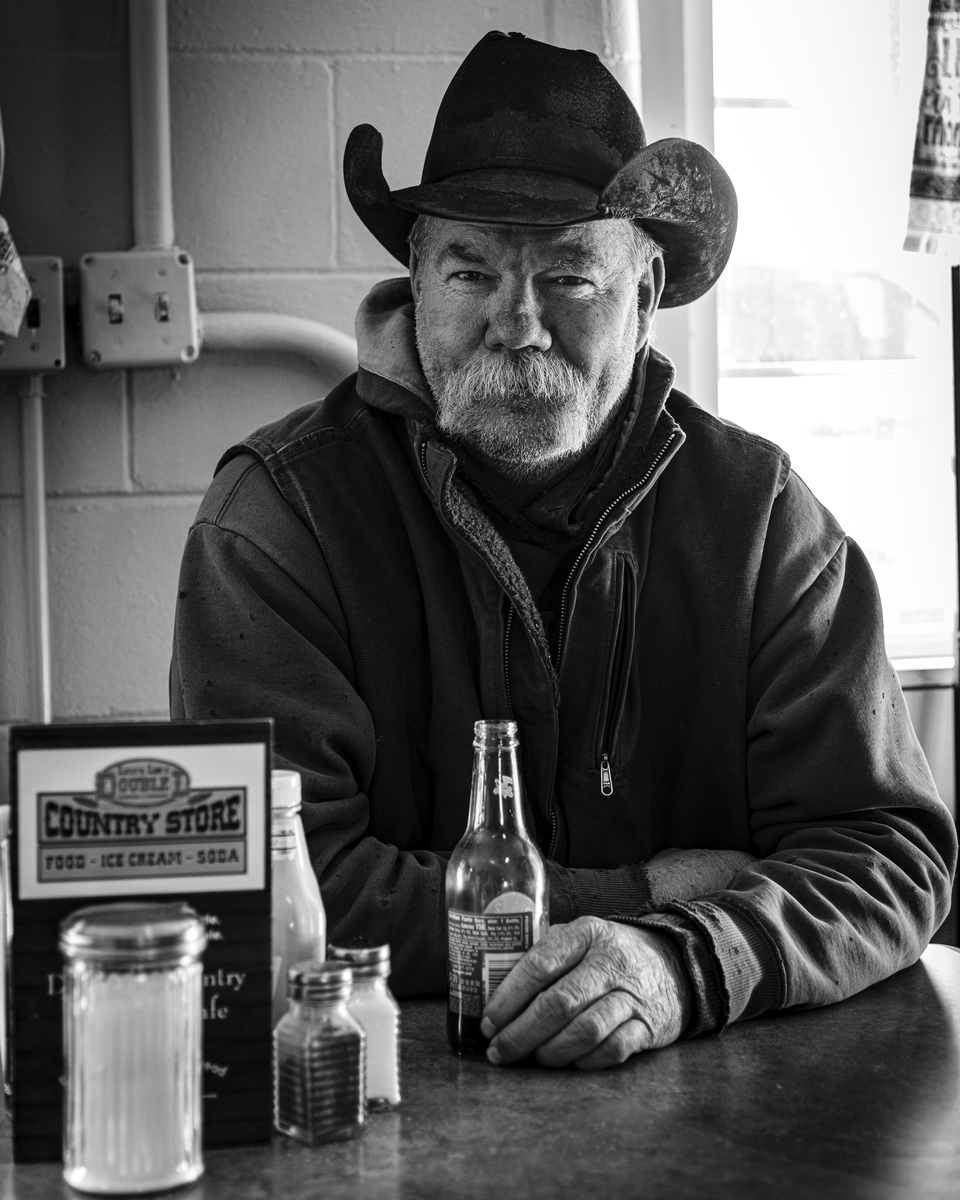

More importantly, black-and-white removes distraction. Color can dominate an image whether it belongs there or not. A bright shirt, a sign, or a painted wall can pull attention away from the human story in a photograph. When color disappears, the viewer looks at expression, gesture, and relationship. A wedding becomes about emotion rather than decoration. A portrait becomes about character rather than wardrobe. A documentary image becomes about truth rather than spectacle.

This is why black-and-white photography continues to endure. It simplifies without reducing. It strips away the decorative layer and leaves structure behind. The viewer fills in the color from memory, which makes the photograph more personal and often more powerful.

Digital technology has made photography faster and more accessible, and it has its place. But true monochrome film still offers something unique: a direct connection between light and image. Different technology, different fingerprint. The debate resembles violinists arguing over a Stradivari and a modern instrument — both can produce music, but they do not produce the same sound.

For me, black-and-white photography is not a stylistic choice. It is a philosophical one. I am not trying to manufacture an image. I am trying to witness light and record it honestly. When the photograph succeeds, it feels less like a picture and more like a memory — not processed, not reconstructed, but seen.